Last time, we discussed how Tombstone more effectively structures its narrative compared to Wyatt Earp. This week, we’re looking at how the conflict development is also more effective in Tombstone. These aspects of storytelling work in tandem, but I think the role of conflict is worth exploring more in-depth on its own merit.

I’ve talked before on here about how vital conflict is to storytelling, and it’s something I frequently discuss with my authors. In quite a few manuscripts I’ve read as an editor, one of the first things I notice is that there is no conflict. Everyone gets along. The villain is quickly dispatched, and the characters are all nice people. This is an ideal situation in real life for most people, but it’s a killer for narratives.

The Importance of Conflict

Conflict is absolutely vital for narratives!

It doesn’t have to be high stakes in the grand scheme of things, per se, depending on the story and the genre, but it has to be there as a guiding force for the action and it needs to be high stakes for the characters. It’s what propels the plot forward and also cultivates the characters’ development.

Tombstone’s Use of Conflict

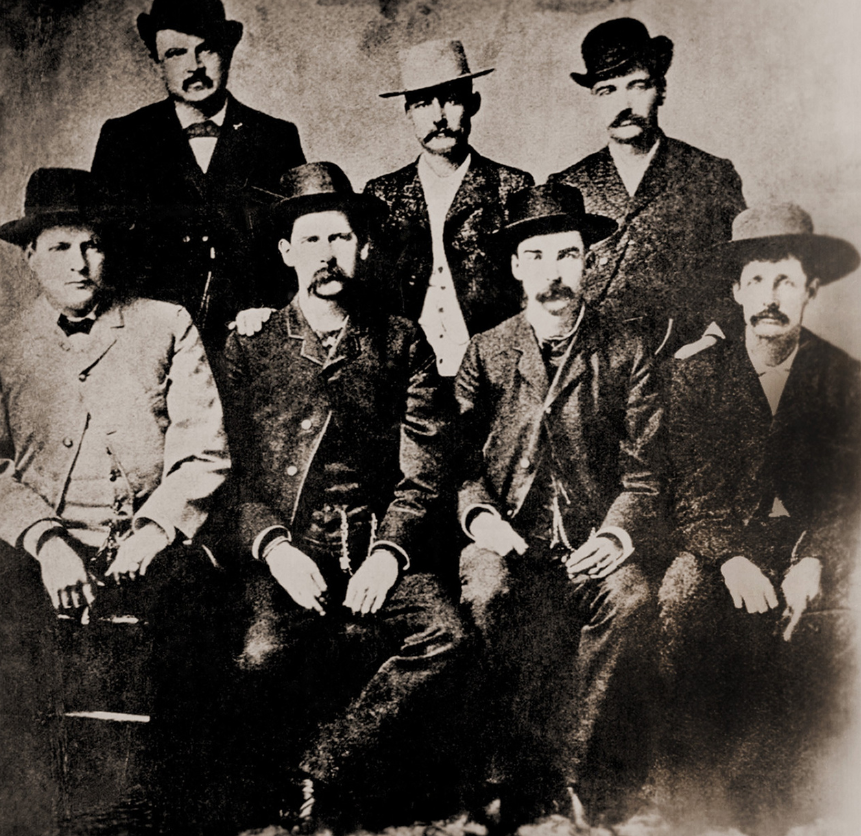

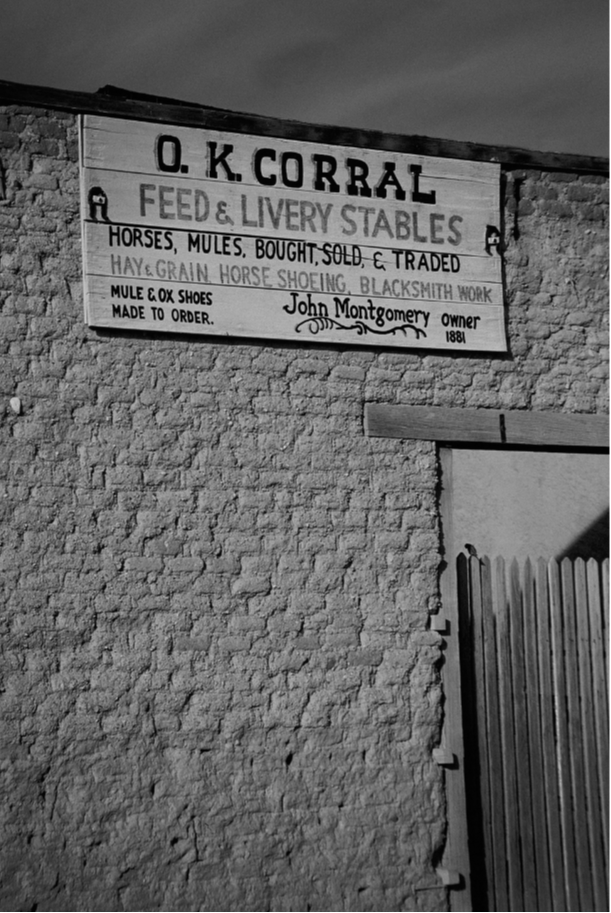

Because of the sharper focus we discussed last time, Tombstone does a great job of developing conflict throughout the movie. By devoting almost all of its runtime to introducing us to the major players in Tombstone, letting the audience watch the start of the conflict between the principal characters, and following the conflict to its natural resolution, the movie amply develops that central conflict. Even if you don’t like the movie, you’re not going to watch Tombstone and end it not knowing why those guys hated each other or the personalities of the main characters on both sides.

Conflict Among Allies in Tombstone

I’ll discuss more about the conflict with the main antagonists in the next blog post, but even the Earp-Holliday alliance in the movie features its share of conflict. This Wyatt Earp, all in all, is a good guy, but he’s not a perfect guy nor is he eager to be the story’s hero. He’s a better man than his chaotically villainous opponents, but he’s also pretty self-interested. Wyatt and his brothers have heated arguments over what to do about the growing instability in Tombstone. Again, Wyatt may be the protagonist, but he doesn’t have the most conventionally heroic approach to the situation. He’s there to make money, and he’s fine with whatever happening as long as it doesn’t affect his bottom line. He has no interest in being the instrument for instituting law and order. He’s not entirely disinterested, but he knows from personal experience how dangerously these situations can escalate, and he’s done with that.

But that approach starts to really bother his older brother Virgil. The longer he stays, the more it haunts him. And this creates conflict! In fact, it’s quite realistic conflict because both Earp brothers have a point, and in my opinion, that’s the best kind of conflict in a story. Wyatt isn’t wrong that getting involved is going to cause a lot of trouble—the movie proves his argument for him—but Virgil isn’t wrong either that the situation is unsustainable and predatory. (The movie also proves his argument for him.)

In fact, Wyatt’s strong reluctance to return to being a lawman is a recurring source of conflict between Wyatt and many other characters. He’s constantly approached and asked to serve as law enforcement, an offer he repeatedly turns down. The movie effectively intertwines this conflict with his conflict with his brother and the larger conflict within the story as the feud between the Earps and Cowboys becomes so bad that eventually Wyatt has no choice but to get involved.

Watch the Earp brothers effectively butt heads in this scene.

Conflict among the Cowboys in Tombstone

The antagonist Cowboys of course provide their own source of conflict throughout the story in opposing the Earps, but their ranks are also not entirely unified. In one of my favorite scenes, Johnny Ringo—furious over the OK Corral shootout that killed his friends—tries to provoke a fight with the Earps. That could be pretty standard villain-induced conflict, but what makes it especially interesting is that Johnny’s Cowboy friends are actually the ones that intervene to stop him. What then ensues is conflict between Johnny and Curly Bill (and the other Cowboys who round him up). And again both sides have a point. If you put on your proverbial Villain (Cowboy) Hat, Johnny’s not wrong to want to avenge his dead friends. But Curly Bill’s not wrong either to urge him to pipe down for the time being and wait for a more strategic time for revenge.

Watch the Cowboys at odds with each other in this scene.

Wyatt Earp’s Use of Conflict

In my opinion, a lot of what diminishes Wyatt Earp as a narrative is its use of conflict is uneven, underdeveloped, and one-sided. The first half of the movie deals a lot with Wyatt’s internal conflict. He doesn’t seem to particularly enjoy being a lawman, and as the movie well demonstrates, it’s not a particularly rewarding job in a roughneck place like Dodge City. He keeps leaving the job and then finding his way back. That’s actually a pretty good premise for conflict in a story. Why does Wyatt keep ending up in these situations doing something he doesn’t want to do? How does that affect him as a character? The movie never really addresses this.

Just as in Tombstone, wanting to do something else is a big impetus for him relocating to Arizona Territory. However, after his business ventures blow up in his face, he returns to his previous profession. That’s actually something I found rather anticlimactic in the movie. He’s spent a good chunk of the runtime talking about wanting to do other things and actually doing them, but once he’s thrown back into this job he doesn’t want, it’s never really discussed again. I think this is also a missed opportunity to explore more facets of Wyatt’s character. Does he actually enjoy it after all? That’s never the sense the movie gives its audience. Does he resent this turn of events? Has he resigned himself to it? Is he so pragmatic he doesn’t even engage in this level of self-reflection? It’s hard to tell.

I believe the reason the movie never quite resolves this is because the movie never seems entirely clear on how it wants to frame Wyatt, other than he became more grim because his first wife died tragically. It shows a much more unlikable, darker Wyatt than Tombstone does, but it also often frames him as a far more conventional and noble hero too. The dichotomy between these two sides of him is never explored, so he often seems underdeveloped rather than complex. I suspect the unclear characterization of Wyatt is a big part of why the moments of conflict in the movie often fall flat because the movie repeatedly depicts conflict without ever having a real focus on what the conflict tells us about the characters. I also think that deep down the movie might be uncomfortable with what it is telling us about Wyatt, so that’s why it presents these scenes but then shies away from their implications.

[As a side note, I am pretty sure this uncertainty about Wyatt is why the ending scene about Tommy Behind The Deuce, which we discussed last time, is so muddled. It leaves audiences unsure of its intent because, 3 hours into the movie, the film itself is still actually unsure of how it’s framing Wyatt.]

Promising but Unfulfilled Conflict in Wyatt Earp

Wyatt does have conflict with others throughout the movie, but it’s again not developed enough to truly be effective. One of the big scenes of conflict is when he and one of his in-laws get into a very heated argument at a family get-together. Now, you might be reading this blog series and wondering if your story has insufficient conflict because it doesn’t involve something as dramatic as the Gunfight at the OK Corral. I don’t agree with that stance at all. Conflict doesn’t have to be epically dramatic in the conventional sense to work. In fact, I love petty domestic drama in stories! People being gloriously petty in historic settings is one of my all-time favorite genres.

So, this outburst in Wyatt Earp intrigued me more so than a lot of the more conventional conflict scenes because it involved some real displays of emotion and even some potentially high stakes for the characters, despite the fact it’s nowhere near as inherently dramatic as a gun battle. His sister-in-law demands to know why Wyatt is dictating the entire family’s actions. But this promising addition of something resembling conflict quickly fizzles out because it’s not developed enough to work. The movie never fleshes out the in-laws beyond them disliking Wyatt. Do they have a valid point? I think so—I don’t think most spouses would be happy in this situation either—but the movie never really addresses their perspective other than them screaming at Wyatt about it. Wyatt’s brothers murmur support for staying in cahoots with Wyatt, which could suggest Wyatt has a point, too, but they don’t have anything to say as the argument gets uglier and Wyatt insults their wives. What do they think about all this, really? Do they regard their brother as a tyrant or do they also see their primary allegiance as to each other rather than their spouses? Again, they’re not developed enough for us to know or even guess. Wyatt immediately dismisses the argument, and that’s pretty much that. It’s hard to be invested in this conflict, despite its initial promise as character-driven conflict, when the movie isn’t interested in it either.

A similar dynamic pops up with the love triangle between Wyatt, his wife Mattie, and his new love interest Josie that develops in Tombstone. To be perfectly honest, this is my least favorite storyline in Tombstone. No offense to Dana Delany, but as Josie, she seems to have wandered in from a completely different movie to me, to do things like cheerily ask Wyatt if he’s happy. Is anybody actually happy in Tombstone, except for Curly Bill and maybe relatively happy-go-lucky-for-an Earp Morgan? I think I’d be more interested in a scene where she asks them that rather than Wyatt. . . . So, I was curious to see how Wyatt Earp handled the same storyline, but again, it pulls its punches when it comes to the conflict this could generate.

In this version of the story, Wyatt more openly dumps Mattie for Josie, but this is after he’s repeatedly made it clear to Mattie that he will never love her. Tombstone makes the infidelity more opaque and implied, but it also approaches Mattie differently. She and Wyatt are clearly not getting along well and the relationship is unraveling already, but there’s no indication that they didn’t once love each other at one point. However, by repeatedly establishing that Wyatt has really just been humoring Mattie all along and that he had long warned her that he would never give her the relationship she wanted, Wyatt Earp lessens a lot of the potential conflict generated from the affair. That’s even in spite of the fact that the movie actually features more overt conflict about it than Tombstone. That Mattie knows what’s going on, but mainly just limits herself to glaring at Josie and making passive-aggressive comments to Wyatt. This Mattie screams a lot at both Wyatt and Josie (and even takes a potshot at Wyatt), but again, the conflict doesn’t land when the narrative has worked so hard to minimize Mattie’s point of view and make their relationship seem so one-sided.

Applying These Lessons to Your Writing

What’s the lessen in all of this? Cultivate your narrative’s conflict throughout the text. Don’t wait to introduce the conflict toward the end of the story. It needs to be a sustaining feature throughout. Also, don’t limit conflict to just between your protagonists and antagonists. There can be lesser degrees of tension between characters that are otherwise allies. Finally, don’t pull your punches with conflict. Let both sides have understandable points of view, even if one side is more clearly in the right than the other ultimately. Artificially imposed conflict for the sake of conflict is never going to work as well as the realistic conflict that can generate from two people who have very different approaches to a situation but firmly believe they’re in the right. Don’t know how to do these things? I can help! These are the types of issues I identify in both developmental editing and manuscript critiques.

What’s Next

Beyond the pacing and narrative structure concern I’ve identified, I believe Wyatt Earp has another pivotal problem I often see in manuscripts. It has a bad guy problem. Namely, its bad guys aren’t very developed or distinctive. Tombstone, however, benefits from having some of the most memorable villains in the genre. We’ll talk more about that and why compelling antagonists are so vital in the next installment of the series.

Tombstone Versus Wyatt Earp series