It’s dawned on me several times that I frequently use cooking and/or food metaphors/similes in explaining concepts about writing and/or publishing to my clients.

Part of it is my background in teaching and tutoring. I have some well-honed examples that just work because they’re easy to relate to, and I’ve carried them over to editing easily. As James Beard noted, “food is our common ground, a universal experience,” so simple examples revolving around food and basic cooking concepts are usually easily understood when you’re using them to make a point.

Part of it is also just that I love to cook and eat, and if I’m going to use an example to make my point, I’m going to default to something that’s fun for me to write about. Furthermore, the more I cook and the more I edit, the more overlap I see between both cooking and writing. The writer Paul Theroux explains it better than I ever could: “Cooking requires confident guesswork and improvisation– experimentation and substitution, dealing with failure and uncertainty in a creative way.” If you’re an author, you probably recognize a lot of the process of writing in that quotation too.

So, here are a few of my most used cooking to writing metaphors and the common writing issues/misconceptions they address.

Water Won’t Instantly Boil (and Neither Will Your Plot)

A common issue I note in fictional manuscripts is that plot complications will sometimes spring forth out of nowhere with absolutely no build-up and then quickly resolve themselves just as abruptly. It’s easy to see where the author is wanting to go with this—an exciting plot twist that takes the reader by surprise—but that specific tactic for doing so doesn’t work because it is so out of left field and so undeveloped. It often is also connected with a general lack of conflict or tension in the story.

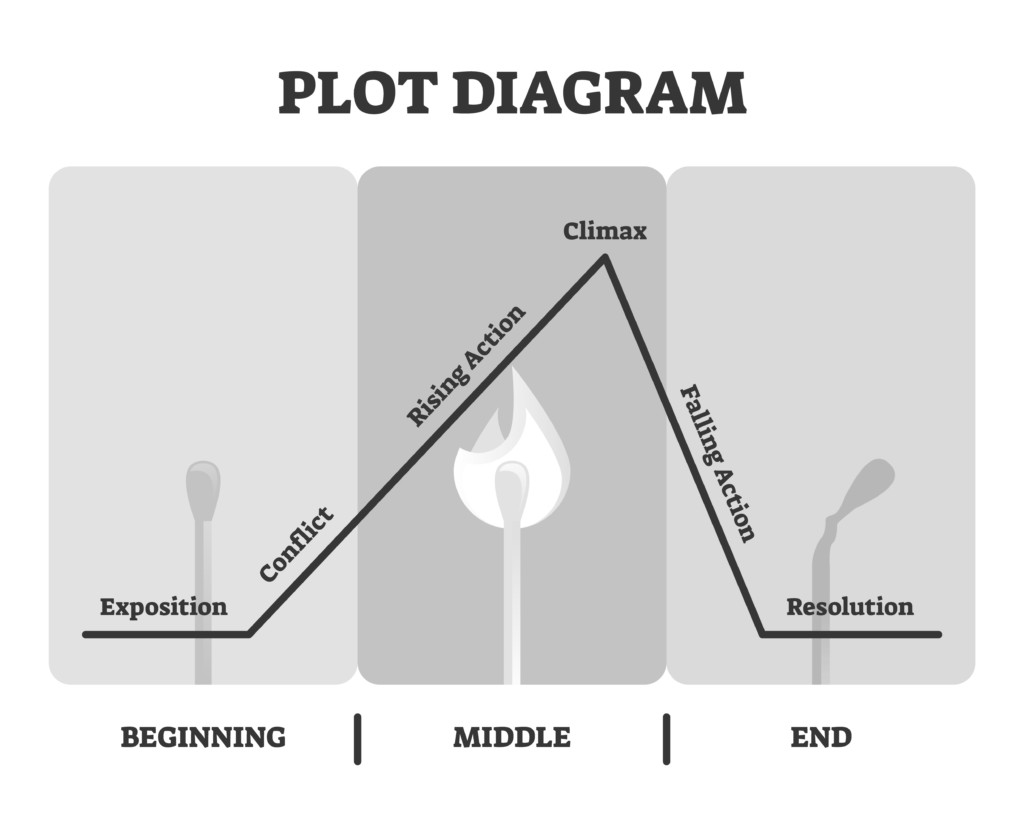

Conflict and tension are vital to stories, and it’s no surprise that storytellers have been using the same elements of plot since ancient Greece—a starting point that escalates with rising action to a critical moment (crisis) that is the peak of dramatic tension before the falling action and resolution kicks in. These elements of plot are all integrally tied to conflict and tension. Without conflict of some form (whether it’s between characters or between characters and nature or between characters and their own inner nature, etc.), there is nothing that will propel the story forward into rising action or a climax. Also, without a conflict that truly challenges the protagonist/protagonists, the resolution is not satisfying to readers. Characters easily besting every challenge thrown at them isn’t particularly interesting to read about.

Ideally the best twists are foreshadowed in such a way that the reader is still taken by surprise when it unfolds but they also can see all the hints and clues they missed (either in retrospect or on a reread). Also, ideally, the source of main conflict is sustained throughout the course of the plot and takes its sweet time before being resolved.

I like to compare narrative in these situations to a boiling pot. That comparison is hardly unique to me, but the idea is that the tension and conflict in a story is very much like a boiling pot of water. Your pot of water doesn’t boil instantly. Even my handy electric kettle that I use for hot tea because it boils water so much faster than a pot on the stove takes a little time to work its magic.

Likewise, before the tension and conflict in your story boil, they need time to get to that point. You have to develop the conflict and tension in a sustained way for it to be satisfying to your readers. It’s not enough for a character to just suddenly make a life-changing decision or for an opponent to spring forth out of nowhere and quickly be bested. One of the best pieces of writing advice I’ve ever heard—and one I employ just as much as my cooking metaphors—is “Make them laugh, make them cry, but more than anything, make them wait.”

If incorporating tension and conflict into your plots is something you struggle with or if you’re unsure of whether your handling of them is effective, this is something I address in both my developmental edits and manuscript critiques.

Cooking Without a Recipe

Writing, like many creative endeavors, is a messy enterprise. Just because you sit down to write, say, a mystery doesn’t mean you end up with a mystery. In the course of writing that mystery, you may end up writing a romance or something more traditionally categorized as horror. There’s nothing wrong with genre-bending/multi-genre works, but sometimes there’s a very stark change in tone that accompanies this shift that can be jarring for readers.

This shift in focus is common because, as I like to say, writing is like cooking without a recipe. More specifically it’s like baking without a recipe. It’s the equivalent of setting out to bake a cake with no ingredient list and no step-by-step instructions and then realizing you’ve ended up with something much more like a pie. (Realistically, if you try to make a cake like this, you’re probably not going to get a pie either, but let’s just roll with the comparison for the sake of it.) If you’re actually baking and you try this, whatever comes out of the oven is the end result of your experiment, and you have to either eat your quasi pie or start over again to make a cake.

But in writing, this state of chaos is actually a pretty natural part of the process, and this is where revision kicks in. Revision is the part of writing where you look at that sort-of pie that was supposed to be a cake and decide what you want to do with it. Do you want it to continue being both pie and cake and go back and integrate the elements of both more effectively throughout? Maybe after further thought, you decide the pie is what you want after all or you decide, no, you really did want that cake. Revision allows you do any and all of these things. So, that mystery that became a romance can be revised into a mystery with a strong romance element throughout or it can be revised into a mystery with no romantic elements or it can be revised into a romance with no mystery elements. It’s entirely up to you!

The main thing is just recognizing exactly what the initial draft is and making decisions on what you want to do with it. Depending on the individual manuscript, one revision path may be easier than the other in the amount of time and changes that need to be made. This is something that I can help you with as an editor.

What’s for Dinner?

Another related issue is in terms of marketing books. In the same way that knowing what genre you want your story to be helps in the revision stage, it also is vital for you to be able to communicate that with potential readers when you’re marketing your book.

If you go to a restaurant and order a burger and they bring you spaghetti instead, you’re probably not going to be a happy customer. It doesn’t matter that you also like spaghetti and may well have ordered it before from the same restaurant. It doesn’t even matter that the spaghetti is great. You went there expecting a burger and got something completely different.

Readers can be the same way when their expectations for a book don’t match the book itself. Sometimes that’s out of your control as an author because some people have peculiar and unreasonable expectations about books and nothing you do can change that, but the way you frame a book can make a big difference in ensuring that readers who are considering your book are the people who will likely enjoy the book.

Let’s go back to our example of the mystery manuscript that ended up becoming a romance in the course of the first draft. Let’s say that in the course of revising, you’ve decided to integrate both of those elements into a book that features a strong mystery but also a strong romantic element to go with it. When you’re finally marketing that book, you’ll want to pitch both aspects of that story.

If you only talk about the mystery elements, you’re going to attract mystery readers who may not be interested in reading a mystery with a heavy emphasis on the protagonist’s personal life and then are put off by the book’s equal focus on a romance. In the same way, if you only talk about the romance elements, you’re going to attract romance readers who don’t care about mysteries and are disappointed the romance they’re invested in keeps getting interrupted with dead bodies.

Both of these examples are readers who ordered a burger and got spaghetti.

That’s not to say that some of these readers may not have eventually been in the mood for a romance/mystery or even that the book itself isn’t a great read, but that’s not what the reader was expecting when they picked it up and they’re probably going to be disappointed or even feel a bit tricked. Framing the book as equal parts romance and mystery, however, is going to ensure more readers who are looking for that kind of a book will find it and connect with it versus people who are not as likely to enjoy that combination or are simply not in the mood for it at that moment.

If you have questions about how to market your book or determine what genre it is, let me know! I also have a blog post that talks more about how to write compelling and accurate copy for your book by thinking like a librarian.

What writing issues are you struggling with? Let me know!